Cuban Carnival: Cuba’s Second City Throbs with Conga, Rumba, and Salsa

SANTIAGO DE CUBA, THE FIRST CAPITAL OF CUBA,

IS WHERE SALSA WAS BORN. WITH DEEP AFRICAN

ROOTS, HERE THEY CELEBRATE THE MOST RICHLY

MUSICAL CARNIVAL OF THE AMERICAS.

Outside the bus station, a vast revolutionary plaza stretched out. Lurking to one side was a boxy trishaw with a high passenger seat. The young black driver hissed, “Meet me over there on the corner!” I lugged my bags across the broad avenue and climbed aboard. Instead of gliding down the boulevard into Santiago, we turned up a side street and trundled through poor barrios where shirtless black people idled on the porches of crumbling villas.

“I have to watch out for the police,” explained the sweating pedicabbie. “I’m not supposed to carry foreigners.” Many zig-zags later we hit the city centre, where narrow colonial streets rode upon steep hills. Seeking lodgings, up hill and down dale, my diligent tricyclist knocked on door after peeling-paint door until finally one old lady said “Sí”. I had struck lucky: dear old Tatica became my Cuban auntie.

Now what should I pay this guy? He had worked long and hard in the searing July heat, doing his best to help me, and breaking the law, in order to get the magic door-opener of US dollars. So, knowing it was almost half the typical Cuban monthly salary, I gave him five bucks. “Gracias,” he grinned, happy to add it to his dollar fund, which would gain him entry to a dollar store, full of imported and otherwise unobtainable goods.

Now what should I pay this guy? He had worked long and hard in the searing July heat, doing his best to help me, and breaking the law, in order to get the magic door-opener of US dollars. So, knowing it was almost half the typical Cuban monthly salary, I gave him five bucks. “Gracias,” he grinned, happy to add it to his dollar fund, which would gain him entry to a dollar store, full of imported and otherwise unobtainable goods.

When you know what burdens the locals labour under, when you experience the Caribbean island’s glorious pluses, Cuba’s difficulties for the independent traveller – transport, accommodation and food are all challenges, the dual currency money system is mind-boggling – melt away like the ice in your rum fizz. Cubans are friendly and gracious, the cities are airy, peaceful and straight out of the 50s – 1950s, 1850s, 1750s, whatever. And the music, ah, the music is heavenly.

When you know what burdens the locals labour under, when you experience the Caribbean island’s glorious pluses, Cuba’s difficulties for the independent traveller – transport, accommodation and food are all challenges, the dual currency money system is mind-boggling – melt away like the ice in your rum fizz. Cubans are friendly and gracious, the cities are airy, peaceful and straight out of the 50s – 1950s, 1850s, 1750s, whatever. And the music, ah, the music is heavenly.

Especially in Santiago. The old seaport of Santiago de Cuba lies in the far east of the 1250km-long island, and is Cuba’s second city. Founded by the Spanish conquistadors in 1514, from 1515 to 1607 Santiago was the capital of the colony of Cuba, and ever since has been the main city of Oriente, the eastern province. Pirate attacks prompted the construction of the mighty El Morro Castle at the mouth of Santiago Bay. Copper from nearby mines was Santiago’s main export, African slaves for working the sugar plantations were its chief import, to its shame, but eventually to the world’s immense cultural benefit.

With its large natural harbour, an inlet in the mountainous coast, Santiago developed as the port and commercial centre for the sugar and rum industry, with a large black population. A culture of mixed Spanish, French and African origins brewed throughout the 19th century and blossomed in the 20th. Musical styles blended from African percussion and European melodic instruments – “the love affair of the African drum and the Spanish guitar” as the Cuban musicologist Fernando Ortiz said – were born and raised.

HOME FROM HOME

In Tatica’s bric-a-brac scattered patio, a parrot squawked in a cage. “Ay, mucho calor!” – “Phew, it’s hot!” Tatica exclaimed, and I had to agree. But I didn’t care how barbecued I might get; I already felt I was somewhere very special, zoomed deep into the heart of Afro-Cuba and the Spanish Caribbean – and strangely, wonderfully at home. “Shall I make you a lunchette?” offered my new auntie, with that Hispanic love of the diminutive. There duly arrived a whacking meal of beans, pork, rice and avocado.

“So, Tatica, does carnival start today?” That was really what I had come for. Santiago’s carnival is Cuba’s best and the Caribbean’s most vibrantly musical celebration. Idiosyncratically, it takes place not six weeks before Easter like everywhere else in the world but in late July. That’s because it celebrates St. James the Apostle, the city’s patron saint, whose day is July 26. It was also the day in 1953 when Fidel Castro’s revolutionary band used the distraction of carnival to launch their first attack, on Santiago’s Moncada barracks.

“So, Tatica, does carnival start today?” That was really what I had come for. Santiago’s carnival is Cuba’s best and the Caribbean’s most vibrantly musical celebration. Idiosyncratically, it takes place not six weeks before Easter like everywhere else in the world but in late July. That’s because it celebrates St. James the Apostle, the city’s patron saint, whose day is July 26. It was also the day in 1953 when Fidel Castro’s revolutionary band used the distraction of carnival to launch their first attack, on Santiago’s Moncada barracks.

“Sí, sí,” swore my Cuban auntie, “carnival starts tonight.” Much heartened, I strolled out to the tree-shaded Plaza de Dolores (Sorrow Square), which proved anything but mournful. On one corner, guitar and bongo rang out through an antique blackened wood grille. Inside the dark and cigar-fumed Café La Isabélica, a trio played for tips, a man rolled fresh cigars, and a local cafe society downed shots of strong black coffee, grown in Oriente’s mountains.

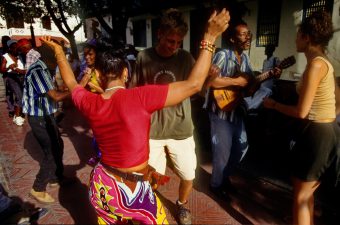

Out in the square, a five-piece combo including double bass and congas was playing rhythmic delights from the inexhaustible Cuban songbook. Passers-by started playful courtship dances in the rumba tradition (not the ballroom dance!) which comes directly out of the old slavery days, the African-derived partying the slaves enjoyed on their Sundays off.

Moving further up the tiled square, I heard more music coming out of a fine colonial building, hosting the Taberna de Dolores restaurant. Cue for lunch, choice of fried chicken or fried chicken – but you could pay in pesos, the local currency, with which everything is dirt cheap, so I could afford a whole battery farm. This place was once a Spanish merchant’s warehouse, above which the family lived. In the palm-shaded courtyard, a bunch of old timers played boleros, the slow romantic songs redolent of the 50s, Besame Mucho and Dos Gardenias Para Ti, a tradition revived to worldwide acclaim two decades ago by Ibrahim Ferrer of the Buena Vista Social Club.

And where was cute old Ibrahim from? Santiago de Cuba – born directly into music at a social club dance!

Santiago de Cuba is a fount of much of what is great in Cuban music.Many of the best musicians have hailed from here. The bongo drum was invented here. The son (pronounced as in ‘sonic’), Cuba’s main musical form, was conceived in Oriente, honed in Santiago, polished in Havana, took a plane to New York, and became salsa. As New Orleans is to jazz, so Santiago is to salsa.

DO THE CONGA!

A percussive explosion hits Tatica’s house. Conga! Night has fallen, carnival has begun, the neighbourhood comparsa is on the move. I step out into the throng and the thrill of the hypnotic conga beat: a dozen men hitting skin and steel in a mesmerising rhythmic clatter rooted in Africa. Up front, the steel beaters lead the way with cowbells and hoe blades out of the old plantation days, capped by the mighty clang of the anchor man rapping a steel rod on a cast-iron brake drum. Next come the hand drums – deep tumbadoras, wide bombons – and bead-clad shakers, and all around clamour the conga dancers, sideshuffling, hip-swinging, abandoned to the rhythm and spirit of carnival. Me too, oh wow, me too! This is the world’s greatest therapy, the healing drum, the dance trance.

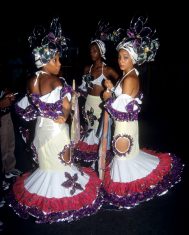

Up and down the hills, past colonial façades, through elegant squares goes the conga, gathering steam and numbers as it goes, heading for the carnival parade ground, a major boulevard flanked by grandstands. There, spontaneity gives way to choreography. Costumed dancers sail forth, outfitted in gaudiness and glitter, in tinsel-and-cellophane hats shaped like streetlamps or pineapples, sashaying down Avenida Garzon. Older folk from the cabildos, the old slave associations, dressed in 1800s style – white suits, billowing gowns – dance the stately contradanza.

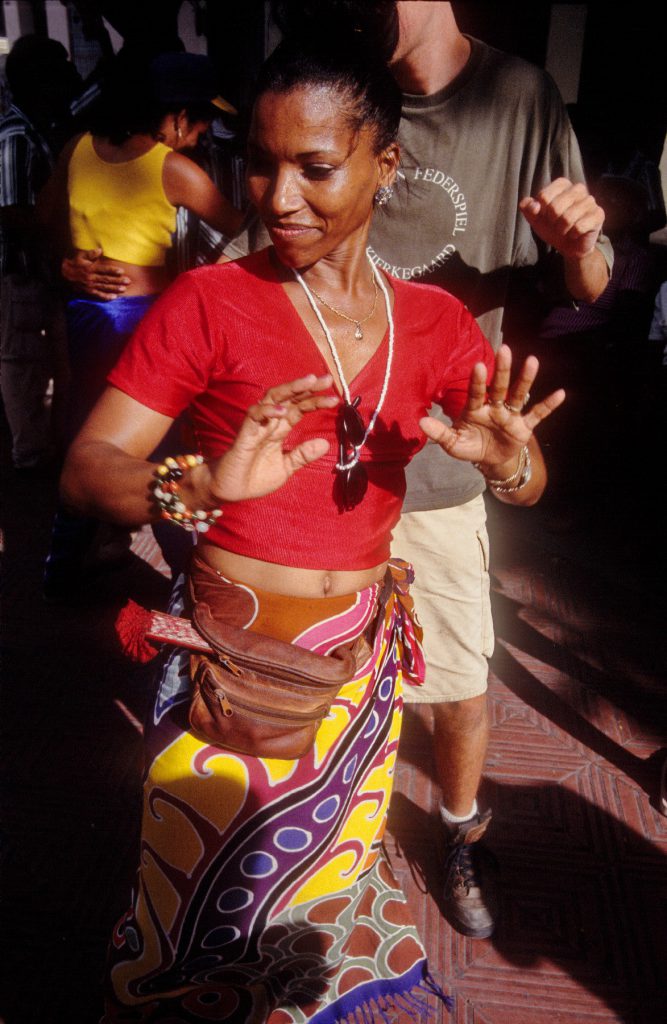

That’s the glitzy bit, the nights of Caribbean theatricality, but the musical bits fill every day, and wonderful they are. In searing sunlight in the main square, Plaza Cespedes, beneath the old town hall from whose balcony Fidel Castro proclaimed the revolution’s victory on New Year’s Day, 1959, vividly dressed folkloric groups leap and swirl in dramatic performance. Descendants of slaves, the troupes act out dramas of slavery days and Afro-Cuban religious ceremonies praising the orishas, or gods, spurred by conch and drums, chants and cries.

In shopping streets, parks and squares, music combos play each morning and afternoon, gathering passers-by in celebration. Old guys croon boleros and sons, shaking maracas, slapping double basses, plucking tres guitars. Voices and drums ring out with messages rooted in the distant past of Africa. “Cuban music is voices and drums, the rest is a luxury,” goes the saying.

DANCING IN THE STREETS

Three conga players beat interlocking rhythms, a blind man sings a soaring lead in an Afro-Spanish dialect, a chorus of young women chants responses, passers-by start playful courtship dances. Rumba, it’s called, the direct descendant of the music the slaves consoled themselves with on their Sundays off. Again, make no mistake, this is not the corny ballroom dance.

Rumba is the improvised acoustic music of Afro-Cubans, struck up in homes and neighbourhoods whenever people feel the need. Just congas, shakers and voices can do the job, whose roots lie deep in the sacred music of the Afro-Cuban religions like santeria, abakua and congo.

These are the profound musical sources of Santiago de Cuba, which give rise to the intense musicality of Santiago de Cuba’s carnival. People dance in the streets and squares with a joy in the music that is their own, that is in their blood, that is their life and soul.

These are the profound musical sources of Santiago de Cuba, which give rise to the intense musicality of Santiago de Cuba’s carnival. People dance in the streets and squares with a joy in the music that is their own, that is in their blood, that is their life and soul.

In the Casa de la Trova, the traditional music club which is found in each Cuban city, combos play morning, afternoon and night, free for Cubans, two pesos for tourists. One afternoon, an all-woman septet swings through an up-tempo repertoire, drawing curious crowds to the wooden window grilles of the old colonial building in historic Heredia Street.

On a street corner, the piercing wail of the Chinese cornet spouts from a black man in a scarlet jumpsuit with billowing frilly sleeves. It’s Valentin, the virtuoso of la corneta china, an eternal character of the Santiago carnival, accompanied by cowboy-hatted Alias Bocu on bata drum, amiable rum-soaked fixture of the Santiago streets. Valentin plays so brilliantly, so creatively, that a visitor from Havana comments, “He’s a genius.”

CRADLE OF THE REVOLUTION

Two themes dominate Cuba: music and revolution. Especially in Santiago. The Moncada Barracks are preserved as a museum of the revolution, down to the 1953 attack’s bullet scars. Guides explain exhibits, including guerrilla lunch boxes and blood-soaked fatigues, with a deeply held respect for the bravery of those who overthrew Batista’s corrupt

tyranny.

The conspirators of the Moncada attack met the night before at the Hotel Rex. This still exists in renovated Art Deco glory, and the room in which two attack leaders slept is never let but preserved as it was on that night. Urban rebellion had to give way to serious guerrilla war in the mountains for the revolution to succeed: the rugged Sierra Maestra mountains which loom large on the far side of Santiago Bay. There in 1956, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and a dozen others began the laughable project of militarily capturing Cuba. Less than three years later, on New Year’s Day 1959, Castro was standing on the balcony of Santiago town hall to wild and rapturous acclaim as Batista fled the country. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive! Now the revo is a daily struggle, albeit underpinned with low rents, cheap food, and free education and healthcare. Cruising one day in a magnificent 1953 Chevy, one of Cuba’s common retro-auto miracles, I queried the taxi driver’s add-ons.

The conspirators of the Moncada attack met the night before at the Hotel Rex. This still exists in renovated Art Deco glory, and the room in which two attack leaders slept is never let but preserved as it was on that night. Urban rebellion had to give way to serious guerrilla war in the mountains for the revolution to succeed: the rugged Sierra Maestra mountains which loom large on the far side of Santiago Bay. There in 1956, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and a dozen others began the laughable project of militarily capturing Cuba. Less than three years later, on New Year’s Day 1959, Castro was standing on the balcony of Santiago town hall to wild and rapturous acclaim as Batista fled the country. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive! Now the revo is a daily struggle, albeit underpinned with low rents, cheap food, and free education and healthcare. Cruising one day in a magnificent 1953 Chevy, one of Cuba’s common retro-auto miracles, I queried the taxi driver’s add-ons.

“You didn’t mention that when we fixed the price,” I moaned. “We Cubans are in a battle,” he cheerily responded. “Yes, but why battle against me when you’ve already got a good price?” I wanted to say, but let it drop.

As a tourist in the current Cuban economy, you switch between paying way over the odds (e.g. inter-city bus fares) to paying almost nothing (coffee in a stand-up bar, 1 US cent). Win a few, lose a few.

DRINK UP!

Santiago is much closer to Jamaica and Haiti than it is to Florida, and this is rum territory. The Bacardi family started its distillery in the city in 1862, decamping to Puerto Rico after the revo. No problema, there are plenty of other brands for mixing your daiquiri or mojito and the state rum monopoly’s vast warehouse down by the port holds 42,000 barrels.

Just down the coast is a pretty little bay called Daiquiri where American troops landed in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Quickly taking to the local rum, crushed ice and lime tipple, the invaders called it ‘daiquiri’ and a classic cocktail was born. Cuba Libre – rum and Coke – dates from the same epoch, celebrating Cuban independence from Spain and alliance with the USA, though that soon turned to Coca-colonisation. It took the 1959 revolution to put the freedom fizz back in Cuba Libre – which soon had to be made with Soviet soda.

Just down the coast is a pretty little bay called Daiquiri where American troops landed in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Quickly taking to the local rum, crushed ice and lime tipple, the invaders called it ‘daiquiri’ and a classic cocktail was born. Cuba Libre – rum and Coke – dates from the same epoch, celebrating Cuban independence from Spain and alliance with the USA, though that soon turned to Coca-colonisation. It took the 1959 revolution to put the freedom fizz back in Cuba Libre – which soon had to be made with Soviet soda.

In communist Cuba, even carnival is state-organised – the Party throws a party. City hall sends beer tankers to the barrios (neighbourhoods) to pump out fresh cold draught and dance bands to pump out live salsa. The streets fill with revellers and turn into dance floors. In upmarket Heredia Street, it’s bottles of Havana Club rum and scintillating son from the Septeto Santiaguero. Tight-skirted jineteras (hookers) dance with tourists trying to be Cuban.

The barman takes a plastic cup, sticks in a sprig of mint, squeezes a lime over it, splashes a good dose of rum, sprinkles some castor sugar, and sets to mashing. Then in goes ice and soda water, and with a vigorous stir your mojito is alive. The bongo raps out, the bass comes in under, a trumpet soars above, the congas start motoring, and you’re on the floor again, driven by rum ‘n’ rhythm and that inimitable Cuban spirit.

Viva Cuba! Viva Santiago de Cuba!

FACTS : SANTIAGO DE CUBA TRAVEL FILE

GETTING THERE

Southeast Asia to Cuba: The gateway is Havana, Cuba’s capital. Air France (www.airfrance.co.th) flies there via Paris; Air China (www.airchina.com) flies via Beijing; Turkish Airlines (www.turkishairlines.com) flies via Istanbul.

Havana to Santiago: the distance is 880 km, with planes, trains and buses available. Air: Cubana operates the route, details at www.cubana.cu and www.cubajet.com. Bus: Viazul (www.viazul.com) luxury coach takes about 15 hrs, US$51 one-way. Train: Takes around 16 hrs, fare CUC$30 one way, but only runs every four days; visit www.seat61.com/Cuba.htm for details.

GETTING AROUND

Santiago’s city centre is quite compact so it’s easy to walk around. For trips out of town or to the suburbs, use taxis. Buses are very crowded and infrequent, so best avoided.

WHEN TO GO

Santiago Carnival takes place in late July; the 2017 dates are July 22-28. This is the hottest time of year in Cuba with highs in the mid-30s. From July 1st to 8th annually, Santiago holds the Festival of Caribbean Culture (a.k.a. Fiesta del Fuego or Fire Festival), also featuring many dance and music performances. Cuba’s tourist high season is December to April, when it is dry and balmy (highs in the mid-20s); July is relatively uncrowded.

WHERE TO STAY

The stately Hotel Casagranda (www.cubahotelreservation.com; www.hotelcasagranda.com) is the ideal address, located on the main square. The Melia Santiago de Cuba (www.solmelia.com) is the best equipped hotel but is outside the centre. The modest Hotel Rex (www.cubaism.com/en/hotels/view/hotel-rex/537) is located at Plaza de Marte in the heart of carnival festivities. Private rooms starting at CUC$20 provide the main budget accommodation, identified by a blue triangle sign outside the house. For pre-booking, try www.casaincuba.com, www.homestay.com and www.airbnb.com

CURRENCY

Tourists must use the Cuban convertible peso (CUC$), which is fixed at US$1. Note that Cuba is a cash economy and you need plenty of bank notes. However, US dollar exchanges incur an extra 10% commission, so it’s better to carry euros or pounds sterling. Credit cards (not from US banks!) can only be used at top hotels, shops and restaurants.